Kapitalmarktausblick 01/2023

Geopolitik, Inflation, Zinsen – Quo vadis, Kapitalmarkt?

Nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg gab es zwar etliche Krisen, aber niemals so viele gleichzeitig wie heute: Putins Krieg, Energiekrise, Inflation, Deglobalisierung, Erderwärmung, rekordhohe Verschuldung, Corona, China, … . Es gibt aber auch einige Lichtblicke, die wir beim heutigen Blick auf die nächste Dekade aufzeigen möchten.

Es ist vermutlich kein Zufall, dass der Index der wirtschaftspolitischen Unsicherheit nach 20 Jahren Seitwärtsbewegung ab 2008, dem Beginn der Finanzkrise, deutlich angestiegen ist (Grafik 1). Die schon zum damaligen Zeitpunkt hohe Verschuldung brachte das weltweite Finanzsystem nach der Pleite der US-Investmentbank Lehman Brothers an den Rand des Zusammenbruchs, der nur durch massives Gelddrucken vieler Zentralbanken vermieden werden konnte. Im Jahr 2011 musste die Europäische Zentralbank, die sich in der Finanzkrise noch geziert hatte, ebenfalls durch Gelddrucken den Euro retten, denn Italien und Spanien standen vor einer Staatspleite. Im weiteren Verlauf der Finanzkrise verloren nur wenige Investmentbanker, aber Millionen „normale“ Amerikaner ihre Häuser und durch die Globalisierung verschwanden außerdem in Ländern wie den USA und Großbritannien viele Industriearbeitsplätze. Dadurch konnten Populisten wie Donald Trump oder Boris Johnson, der Großbritannien in den Brexit trieb, mit den Stimmen der Verlierer an die Macht gelangen. Später mussten die Regierungen zur Bewältigung der Corona-Pandemie erneut hohe Schulden aufnehmen und die Zentralbanken druckten erneut viel Geld. Damit war die Voraussetzung für hohe Inflationsraten geschaffen worden, die durch Putins Angriffskrieg gegen die Ukraine mit der Folge steigender Energiepreise insbesondere in Europa und auch in Deutschland Rekordwerte seit über 50 Jahren erreichten (Grafik 2b).

Inzwischen zeigen sich jedoch einige positive Entwicklungen. Trump, Johnson und der brasilianische „Tropen-Trump“ Bolsonaro haben die letzten Wahlen in ihren Ländern verloren. 60% der Briten sind längst der Überzeugung, dass der Brexit ein Fehler war (Quelle: Welt, 17.02.2022). Weitere Austritte aus der EU sind vorerst sehr unwahrscheinlich geworden.

Die Kapitalanleger haben gelernt, wie schnell die Zentralbanken große finanzielle Krisen in den Griff bekommen können, so dass der Kurssturz an den Aktienmärkten zu Beginn der Corona-Krise nur wenige Wochen dauerte und von einer schnellen Erholung abgelöst wurde, weil erneut viel Geld gedruckt wurde. Die Regierungen haben mit diesem Geld die sozialen Folgen der Lockdowns geschickt abgemildert.

Entgegen den Befürchtungen im Herbst letzten Jahres erfordert die Corona-Pandemie keine besonderen Maßnahmen mehr; in Deutschland wird ab Februar die Maskenpflicht beim Zugfahren aufgehoben.

Auch die Angst vor einem Gasmangel in diesem Winter erwies sich als übertrieben. Politik, Verbraucher und Unternehmen waren wie in jeder Krise flexibel und anpassungsfähig; die deutschen Gasspeicher sind im Januar 2023 mit über 90% überdurchschnittlich gut gefüllt (Quelle: Handelsblatt online, 17.01.2023).

Ungelöst ist bisher das Problem des Angriffskrieges Russlands, der bisher überraschend erfolglos blieb. Der mächtige Putin, der von vielen Populisten bewundert wurde, muss inzwischen selbst um seinen Job fürchten. Die entschlossenen Sanktionen gegen Russland und die hohe Effizienz westlicher Waffen dürften auch Xi Jinping, den Diktator von China, beeindrucken, so dass die Gefahr eines chinesischen Angriffs auf Taiwan etwas geringer geworden sein dürfte. Allerdings verschärft der Krieg das Problem der Deglobalisierung, da man insbesondere in Europa im Zusammenhang mit der Energieversorgung erkannt hat, wie gefährlich es ist, wenn man bei wichtigen Rohstoffen von einem möglichen Gegner stark abhängig ist.

Schließlich sind die Schuldenberge, die am Anfang der beschriebenen Krisenserie seit 2008 standen, seither weiter kräftig angestiegen (siehe Grafik 6a) und werden bei steigenden Zinsen die Staatshaushalte künftig stark belasten. Die Politik vertuscht die Aufnahme zusätzlicher künftiger Schulden. Da gibt es einen Finanzmarktstabilisierungsfonds (480 Mrd. €), einen Wirtschaftsstabilisierungsfonds (250 Mrd. €), ein Sondervermögen Bundeswehr (100 Mrd. €) und diverse weitere „Sondervermögen“. Dabei handelt es sich allerdings nicht um „Fonds“, oder „Vermögen“, sondern schlicht um die staatliche Bereitschaft, in der genannten Höhe weitere Schulden aufzunehmen (Quelle: Prof. Hans-Werner Sinn in der Wirtschaftswoche, 20.01.2023). Auch die Erderwärmung wird in den nächsten Jahrzehnten hohe Kosten und wachsende staatliche Subventionen verursachen. Darauf gehen wir später noch ein.

Nun betrachten wir zunächst das Inflations- und Schuldenproblem. Grafik 2a zeigt die Performance der für einen deutschen Anleger wesentlichen Anlageklassen seit 1970. Aktien haben sich mit Abstand am besten entwickelt, aber auch Gold, Staatsanleihen und Wohnimmobilien sind deutlich stärker als die Konsumentenpreise gestiegen.

In den beiden Phasen mit hoher Inflationsrate (Grafik 3a: 1970 bis 1980, Grafik 3b: ab 2020) sieht die Rangliste allerdings anders aus.

In beiden Fällen (Grafik 3a, b) steht Gold an der Spitze und Wohnimmobilien auf dem dritten Platz vor dem Konsumentenpreisindex. Renten haben sich jedoch ab 2020 mit Abstand am schlechtesten entwickelt, während sie bis 1980 immerhin den zweiten Platz eingenommen hatten. Dagegen haben sich Aktien bisher wesentlich besser geschlagen als in den 70er Jahren. Für die unterschiedliche Entwicklung von Aktien und Renten gibt es Ursachen, die auch in den nächsten Jahren wirksam sein und später erläutert werden (siehe Grafik 10a, b).

In den USA scheint die Inflationsentwicklung der letzten Jahre sehr ähnlich wie in den ersten Jahren der Inflationsdekade ab 1970 zu verlaufen (Grafik 4a). Der Zins lag in dieser Zeit mal über, mal unter der teilweise zweistelligen Inflationsrate (Grafik 4b). Erst als der Zins zweistellig wurde und damit Sparen wieder attraktiv war (Grafik 4b, grünes Oval), sank die Inflationsrate stark und die 40-jährige Phase niedriger Inflationsraten begann (siehe dazu auch den Kapitalmarktbericht vom Oktober 2021 (letzte Seite, den Sie hier finden). Heute liegt der Zins dagegen seit drei Jahren unter der Inflationsrate (Grafik 4c), so dass vom Zins keine nennenswerte inflationssenkende Wirkung ausgeht.

In Deutschland war der Verlauf der Inflation in den 70er Jahren mit einem Spitzenwert von 7,5% deutlich moderater als zur selben Zeit in den USA, wo Anfang 1980 fast 15% erreicht wurden, aber auch schwächer als seit 2020 (Grafik 5a). Die wesentliche Ursache dafür zeigt Grafik 5 b. Der Zins war in der gesamten Inflationsdekade anders als in den USA deutlich höher als die Inflationsrate und auch weitaus höher als heute (blaue Linie in den Grafiken 5b und c), was die im Vergleich zu heute wesentlich bessere Rentenperformance der 70er Jahre erklärt. Durch den damals hohen Zins in Deutschland wurde erfolgreich ein permanent inflationssenkender Druck erzeugt. Heute ist das Bild in der Eurozone (Grafik 5c) ganz ähnlich wie in den USA (Grafik 4c). Der Zins liegt seit Jahren unter der Inflationsrate.

Die Ursache dafür liegt nicht darin, dass die Geldpolitik nicht mehr von der Bundesbank gemacht wird, sondern in der im Vergleich zu den 70er Jahren extrem hohen weltweiten Verschuldung (Grafik 6a). Im Jahr 1981 hatte in den USA und in Deutschland der nachhaltige Rückgang der Inflationsraten eingesetzt (Grafik 2b), aber auch in den anderen Industrieländern. Der wesentliche Grund dafür war das rekordhohe langfristige Zinsniveau am Ende der 70er Jahre (Grafik 6b), das dadurch ermöglicht wurde, dass die Staatsverschuldung im Jahr 1980 überall viel niedriger war als heute (Grafik 6a).

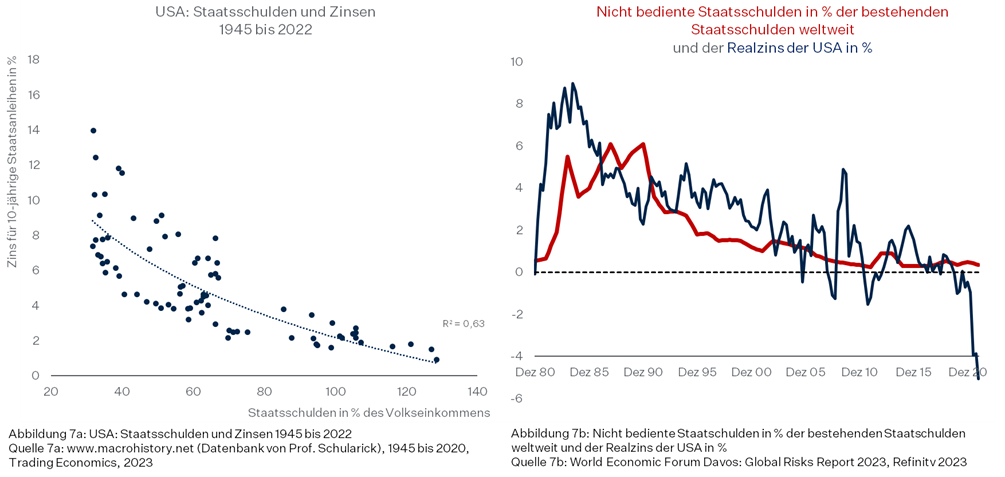

Es gibt nämlich seit 1945 einen statistisch engen Zusammenhang zwischen der Höhe der Staatsverschuldung in % des Volkseinkommens und dem Zinsniveau langlaufender Staatsanleihen (Grafik 7a, der mit der Zahl R² genannte Wert von 0,63 für die USA zeigt einen recht engen Zusammenhang der beiden Größen an; R² kann zwischen Null (kein Zusammenhang) und 1 (maximaler Zusammenhang) liegen). Auch in den meisten anderen gezeigten Ländern existiert diese Mechanik. Der Wert von R² liegt dabei zwischen 0,77 (Japan) und 0,31 (Großbritannien). Für den Zusammenhang zwischen Staatsverschuldung und Zinsniveau gibt es eine klare betriebswirtschaftliche Logik, die auch von Politikern gut verstanden wird. Hohe Staatschulden bleiben nur dann unproblematisch, wenn der Zins in solchen Zeiten sehr niedrig ist, wie nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg oder eben heute.

Dies zeigt sich in der Praxis sehr deutlich. Als der Realzins ab 1980 in die Höhe schnellte, begann weltweit mit kurzer Verzögerung eine Phase mit erheblichen Ausfällen staatlicher Schuldner (Grafik 7b zeigt den US-Realzins, der weltweit die größte Bedeutung hat). Erst ab 1990, als der Realzins schon wieder gesunken war, ebbte die Welle von Staatspleiten allmählich ab. Seit die Realzinsen als Folge der lockeren Geldpolitik zur Eindämmung der Finanzkrise 2008 kaum noch über Null lagen, gab es trotz hoher und weiter steigender Staatsverschuldung fast keine Ausfälle von Staatsanleihen mehr.

Beunruhigend ist jedoch die Tatsache, dass die erheblichen Ausfälle von Staatsanleihen nach 1980 (Grafik 7b) bis 1990 zu über 80% die Staatschulden von Industrieländen betrafen (Quelle: World Economic Forum Davos: Global Risks Report 2023, S. 18), obwohl die Industrieländer 1980 im Vergleich zu heute nur sehr geringe Staatsschulden hatten (Grafik 6a). Auch die Gesamtverschuldung inklusive der Schulden von Privaten Haushalten und Nichtfinanziellen Unternehmen war 1980 weitaus niedriger als 2021 (Grafiken 8a, b).

Schon die im Verhältnis zur Wirtschaftsleistung massiv gestiegenen Staatsschulden erfordern besondere Vorsicht der Zentralbanken bei Zinssteigerungen, damit finanzielle Probleme von Regierungen beherrschbar bleiben. Deshalb haben die EZB und die Bank of England im letzten Jahr nach einem Zinsanstieg von 300 Basispunkten in Italien und 350 Basispunkten in Großbritannien die „Nerven verloren“ und trotz steigender Inflation Geld gedruckt und die jeweiligen Staatsanleihen gekauft (Grafik 9a).

Im Vergleich zu 1980 kommt aber die überall gestiegene Verschuldung des Privatsektors (Haushalte, Unternehmen) als weiteres Problem hinzu (Grafik 8b). Warum diese Schulden den Regierungen nicht egal sein können, zeigt folgendes Beispiel. Während des Immobilienbooms in den USA bis 2007 stieg die Verschuldung der Privaten Haushalte kräftig an (Grafik 9b). Diese konnten sich erstmals auch bei schwacher Bonität aufgrund staatlicherseits gewünschter laxer Kreditvergaberegeln Geld für Hauskäufe leihen. Ab 2007 konnten viele dieser finanziell schwachen Hausbesitzer ihre Kredite nicht mehr zurückzahlen, so dass die Banken in Schwierigkeiten gerieten. Zur Rettung des Bankensystems musste die US-Regierung ab 2008 hohe Schulden aufnehmen, wie man am Anstieg der roten Linie in der Mitte von Grafik 9b gut erkennen kann. So können sich (nicht nur in den USA) zu hohe private Schulden in Staatsschulden verwandeln. Auch der ab 1990 beispiellose Anstieg der japanischen Staatsschulden (Grafik 6a) ist auf das Platzen einer gewaltigen Immobilienblase zurückzuführen (siehe dazu den Kapitalmarktausblick vom Oktober 2020, den Sie hier finden).

Die historisch rekordhohe internationale Verschuldung wird die Zentralbanken auf Jahre zwingen, den Realzins sehr niedrig – möglichst unter Null – zu halten, damit das weltweite Finanzsystem stabil bleibt. Die Reaktionen der EZB und der Bank of England im letzten Jahr haben dies gezeigt. Anleihen bleiben daher als Anlageform in den nächsten 10 Jahren unattraktiv.

Die verglichen mit den 70er Jahren recht gute Performance von Aktien seit 2020 hat einen etwas überraschenden Grund. Die Schweizer Zeitung Finanz und Wirtschaft zeigt den Anteil des Wachstums der Bruttoüberschüsse der Unternehmen in den USA und in der Eurozone an der binnenwirtschaftlichen Inflation Grafik 10a, b).

Zunächst können wir erkennen, dass diese, anders als die gesamtwirtschaftliche Inflation, die in der Eurozone durch die explodierten Energiekosten zusätzlich zu den binnenwirtschaftlichen Preissteigerungen sogar über der US-Inflation liegt, in der Eurozone viel niedriger ist als in den USA. Der Hauptgrund dafür ist die Tatsache, dass die US-Regierung ab 2020 zur Linderung der finanziellen Folgen der Corona-Krise Geld in Höhe von 25% des US-Volkseinkommens ausgegeben hat (Grafik 11a). Dieses Geld konnte dann ab 2021 mit sinkenden coronabedingten Beschränkungen der Wirtschaft ausgegeben werden und heizte die Inflation kräftig an. In der Eurozone war man wesentlich zurückhaltender; nur Italien und Spanien gaben etwas mehr als 10% des jeweiligen Volkseinkommens aus.

In beiden Regionen hatten viele Unternehmen wenig Probleme, steigende Kosten oft sogar mit einem zusätzlichen Aufschlag an die Kunden weiterzureichen und damit ihre Gewinne, aber auch die Inflation weiter hochzutreiben. Diese rechneten sowieso wegen der Inflation überall mit Preissteigerungen und haben diese kaum wahrgenommen. Daher sind die Bruttogewinne der Firmen in den Entwickelten Ländern Europas und Asiens sowie in den USA auch nach Kriegsbeginn angestiegen (Grafik 11b). Lediglich Chinas Unternehmen litten unter hausgemachten Problemen.

Damit können wir die seit 2020 im Vergleich zu den 70er Jahren bisher bessere Aktienperformance gut erklären (siehe Grafik 3a, b), aber natürlich nicht garantieren, dass das Überwälzen der Kosten für die Unternehmen so einfach bleiben wird wie bisher. Da aber der Inflationsdruck allmählich abnimmt (siehe Grafiken 4c, 5c), dürfte dieses Thema an Bedeutung verlieren.

Ein weiteres Thema, das die Schuldenberge weiter wachsen lassen wird, ist die Klimapolitik. In unserem Kapitalmarktausblick vom August 2021, den Sie hier finden, haben wir leider zutreffend vorhergesagt, dass die Politik den effizientesten und am ehesten bezahlbaren Weg zu einer nachhaltigen Reduzierung des CO2-Ausstoßes nicht verfolgen wird. Dieser besteht in einer weltweit einheitlichen CO2-Steuer mit Ausgleichszahlungen an Personen und Staaten, die sich durch eine CO2-Steuer erhöhte Energiepreise nicht leisten können. Der Tankrabatt ist das intellektuell peinliche Gegenteil davon. Anstatt die gestiegenen Energiekosten verbrauchssenkend und klimaschützend wirken und Geringverdienern Unterstützungszahlungen zukommen zu lassen, wurden durch den Tankrabatt den Besitzern von Autos Subventionen gewährt, so dass diese ihren Verbrauch nicht einschränken müssen. Wer kein Auto hat, bekommt dagegen nichts.

Man verteilt also zwecks Stimmenkauf erneut Geld an möglichst viele Empfänger und beschränkt sich nicht auf die Bedürftigen. Angesichts der Verschuldung ist das ausgesprochen verantwortungslos und verstärkt langfristig die Inflationsgefahren, weil die Fähigkeit zur Inflationsbekämpfung durch steigende Verschuldung weiter ausgehöhlt wird. Eine effiziente und langfristig bezahlbare Bekämpfung der Erderwärmung kann auf diesen merkwürdigen Abwegen nicht erreicht werden.

Dieser fragwürdige Umgang mit dem Geld hat auch etwas mit dem Populismus zu tun. Man möchte nicht nur in Deutschland die Zahl der Verlierer, die einen populistischen Politiker wählen könnten, möglichst klein halten. Möglicherweise sind jedoch die aktuellen Misserfolge der Populisten und Diktatoren der Anfang eines allmählichen Niedergangs dieses Politikstils. Die folgende Grafik 12 zeigt für die USA einen interessanten Zusammenhang seit über 100 Jahren, der den Diktatoren offensichtlich bekannt ist. Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts war die Distanz der politischen Überzeugungen von Demokraten und Republikanern fast so hoch wie heute, man war also in wesentlichen Fragestellungen gegensätzlicher Meinung. Gleichzeitig war die Ungleichheit der Einkommen sehr hoch. Das einkommensstärkste Hundertstel erzielte damals wie heute fast 20% des Gesamteinkommens aller Amerikaner.

Der höchste Wert der Einkommensungleichheit wurde mit 19,6% im Jahr 1929, dem Beginn der Weltwirtschaftskrise, erreicht. Danach begann die Ungleichheit zunächst moderat zu fallen – in der Krise sanken zwar die Unternehmensgewinne, aber auch die Löhne -, um dann im 2. Weltkrieg kräftig zu sinken und erst seit dem Ende des Kalten Krieges wieder zu steigen. Angesichts der Weltwirtschaftskrise und dem Kampf im zweiten Weltkrieg gegen die Diktaturen Deutschland und Japan beerdigten viele Politiker ihre Differenzen, um ihren Staat zu retten; die blaue Linie in Grafik 12 fiel ab 1929 stark. Erst als mit dem Fall der Berliner Mauer und dem nachfolgenden Auseinanderbrechen des Ostblocks alle Probleme beseitigt schienen und durch steigende Firmengewinne die Ungleichheit wieder zunahm (Grafik 13b), stieg auch die Polarisierung in der amerikanischen Politik wieder an. Bis 1989 war das Volkseinkommen in den USA um das Sechsfache stärker gestiegen als die Unternehmenserträge (Dividenden) (Grafik 13a), was die Einkommensungleichheit absenkte, während seit 1989 die Dividenden deutlich stärker als das Volkseinkommen gestiegen sind (Grafik 13b).

Probleme, die den Staat ernsthaft bedrohen, z.B. ein großer Krieg, schweißen also die Politiker und indirekt auch das Volk zusammen. Daher zetteln Populisten und Diktatoren gern außenpolitische Konflikte an. Außerdem waren die amerikanischen Spitzenverdiener damals patriotisch genug, um enorm hohe Spitzensteuersätze von ca. 90% (von 1942 bis 1963, Quelle: Wikipedia: Einkommensteuer (Vereinigte Staaten)) zu akzeptieren, was natürlich die Ungleichheit deutlich dämpfte. Die Hoffnung für die Zukunft besteht darin, dass die erneut großen Probleme, die die westlichen und fernöstlichen Industrienationen bedrohen, nämlich der Putin-Krieg, die wachsende Aggressivität Chinas, die Deglobalisierung und die Erderwärmung, die Polarisierung der Politik nicht nur in den USA wieder verringern. Außerdem wird die demografisch bedingte Arbeitskräfteknappheit durch hohe Lohnsteigerungen die Ungleichheit senken. Schließlich haben die populistischen Politiker bisher überwiegend versagt, was sicher nicht nur den Briten klargeworden ist.

Fazit:

Die bereits seit 15 Jahren wachsende wirtschaftspolitische Unsicherheit in Europa und in den USA ist überwiegend auf die seit 40 Jahren stark steigende Verschuldung der Staaten, Unternehmen und Privaten Haushalte zurückzuführen, die erstmals in der Finanzkrise 2008 die Anfälligkeit des weltweiten Finanzsystems offengelegt hat. Dazu kam ein von den Verlierern der Finanzkrise, aber auch der Globalisierung, ermöglichter populistischer Politikstil, der durch Handelskriege gegen China oder den Brexit zu wirtschaftlichen Schäden geführt hat. Dazu kommen aktuell der Putin-Krieg und die künftigen Kosten der Erderwärmung.

Keines dieser Probleme ist bisher gelöst, aber es lassen sich doch einige beruhigende Entwicklungen aufzeigen. Das Finanzsystem kann mit den seit 2008 weiter gestiegenen Schulden zurechtkommen, wenn die Zentralbanken im Krisenfall einspringen, was sie 2008 und dann auch 2020 wegen der die Staatshaushalte massiv belastenden Corona-Krise erfolgreich getan haben. Der Putin-Krieg hat bisher einen überraschend schnellen Zusammenschluss der westlichen Demokratien und eine Wiederbelebung der NATO bewirkt. Damit und mit der bisherigen Erfolglosigkeit von Putin dürfte die künftige Gefahr militärischer Auseinandersetzungen in Europa, aber auch in Fernost sinken. Der Populismus dürfte künftig an Bedeutung verlieren, da sich die eigentliche Ursache, die seit 40 Jahren gewachsene Ungleichheit, künftig aufgrund demografisch bedingter höherer Lohnsteigerungen abschwächen dürfte.

Die bedrohlich erscheinenden hohen Schulden dürften dazu führen, dass die Zinserhöhungen zur Inflationsbekämpfung moderat ausfallen werden, da sonst die Staaten in finanzielle Probleme geraten werden. Mit Zinsen unterhalb der Inflation bleiben Anleihen eine unattraktive Anlage, aber Aktiengesellschaften kommen damit bisher und vermutlich auch zukünftig erstaunlich gut zurecht.

Wer vor 3 Jahren als Anleger aus €-Sicht genau gewusst hätte:

- Es kommt bald eine Pandemie mit einer stärkeren Rezession als nach der Finanzkrise, zu deren Bekämpfung die Regierungen erneut hohe Schulden aufnehmen müssen

- Dann beginnt ein Inflationsanstieg

- Es folgt ein Krieg in Europa, der die Inflation weiter anheizt und zu kräftigen Zinssteigerungen führt

- Die Versorgung mit Energie- und sonstigen Rohstoffen sowie Zulieferteilen ist insbesondere in Europa gefährdet,

wäre wohl kaum zu der Prognose gelangt, dass die Aktienmärkte dennoch zwischen 4% und 25% zulegen werden (Grafik 14). Er hätte den positiven Effekt von über den Zinsen liegender Inflation auf die Firmengewinne sowie die Anpassungsfähigkeit der Unternehmen unterschätzt.

Den Kapitalmarktausblick können Sie auch hier herunterladen.