Kapitalmarktausblick 04/2023

Rezessionen, Schulden und Kapitalmärkte

Die Gefahr einer Rezession nimmt ab Herbst diesen Jahres insbesondere in den USA zu. Inzwischen äußern auch Mitarbeiter der US-Zentralbank diese Meinung (Quelle: Bloomberg, 13.4.2023). Europa ist vor einer Rezession ebenfalls nicht sicher. In diesem Umfeld werden die Staatsschulden weiter steigen. Dadurch wird die ohnehin begrenzte Bereitschaft der Regierungen und Zentralbanken, die Inflation durch hohe Zinsen zu bekämpfen, zusätzlich reduziert. Die langfristigen Auswirkungen dieser Entwicklungen auf die Kapitalmärkte sind das heutige Thema.

Im März hatte die durch steigende kurzfristige Zinsen ausgelöste Krise einiger kleinerer Regionalbanken in den USA und der Untergang der Schweizer Großbank Credit Suisse weltweit einen deutlichen Rückgang der Zinsen für kurzlaufende Staatsanleihen ausgelöst. Die Zentralbanken und Regierungen in der Schweiz und in den USA hatten mit dreistelligen Milliardenbeträgen die Gläubiger der betroffenen Banken abgesichert und damit die Ausbreitung der Krise gestoppt. Allgemein wurde danach erwartet, dass die aktuellen Zinserhöhungen der Zentralbanken demnächst auslaufen werden, um die Ursache der Bankenkrise zu beseitigen. Mit dem erwarteten Ende der Zinserhöhungen glaubten viele, dass damit auch die Rezessionsgefahren kleiner würden. Wir haben im Kapitalmarktausblick vom letzten Monat, den Sie hier finden, erläutert, warum wir weiterhin eine Rezession ab Herbst 2023 erwarten und den Aktienanteil in unseren Kundenvermögen zunehmend auf konjunkturresistente Aktien ausgerichtet.

Seitdem sind die kurzfristigen Zinsen in den USA erneut stärker gestiegen als die langfristigen und die Zinsstruktur in den USA ist noch tiefer in den inversen Bereich geraten (Grafik 1). Der kurzfristige Zins übertraf den langfristigen erstmals im Juli letzten Jahres (roter Kreis ganz rechts). Seit 70 Jahren folgte daraufhin im Durchschnitt 13 Monate später eine Rezession (Ausnahme: 1966).

Seit mindestens 50 Jahren führt eine Rezession in den USA zu steigenden Staatsschulden (Grafik 2), da die US-Regierung wie auch Japan oder die europäischen Staaten seitdem jede wirtschaftliche Krise durch finanzielle staatliche Hilfen abmilderte. Diese Großzügigkeit wurde für den Staat zunehmend dadurch erleichtert, dass die Zinsen bis 2020, als man für die coronabedingten Finanzhilfen 25% des Volkseinkommens ausgab (Quelle: BCA, Dez. 2021), auf 0,5% gesunken waren (Grafik 3).

Dieses Geld kommt jedoch nach den Krisen nicht wieder in die Staatskasse zurück, wodurch die Verschuldung immer weiter steigt. 1981 waren die USA mit 1.016 Mrd. Dollar bzw. 31,7% des Volkseinkommens (siehe Grafik 2) in Höhe von 3.207 Mrd. Dollar verschuldet (Quelle: www.macrohistory.net, Datenbank von Prof. Schularick, 2023). Im März 2023 sind die Schulden auf das 30-fache des Wertes von 1981, nämlich auf 31.500 Mrd. Dollar angestiegen, das Volkseinkommen aber nur auf das 7,6-fache (Quelle: Trading Economics, 2023). Die Finanzhilfen haben also insgesamt weitaus mehr Geld gekostet, als die nach der Krise wieder wachsende Wirtschaft an Steuerzahlungen eingebracht hat, auch weil anders als bis 1945 (Ende des teuren 2. Weltkrieges) seit 1982 die Spitzensteuersätze bei steigenden Staatsschulden sogar leicht gesenkt wurden (Grafik 4). Die Unternehmenssteuern leisteten 1945 mit 7% des damaligen Volkseinkommens ebenfalls einen erheblichen Beitrag zur Sanierung der Staatsfinanzen, aktuell ist die Unternehmensbesteuerung mit 1,1% des Volkseinkommens erstaunlich niedrig (Grafik 5).

Diese Entwicklungen sind die Gründe für den starken Anstieg der Staatsverschuldung in den USA. Langfristig werden die US-Steuersätze für Unternehmen und Spitzenverdiener steigen müssen.

Die Staatsschulden dürften nämlich schon in wenigen Jahren enorme Zinskosten verursachen. Bisher sind die Zinskosten für den gigantischen Schuldenberg überraschend moderat, nämlich weniger als 2% des US-Volkseinkommens im Jahr 2022 (blaue Linie in Grafik 6, Zahlen direkt von der US-Zentralbank). Auch im Jahr 1980 blieben die Zinskosten unter 2% des Volkseinkommens. Schon 1985 waren sie jedoch auf 3% des Volkseinkommens gestiegen. Die zur Finanzierung der neuen Schulden und zur Tilgung älterer fällig gewordener Staatsanleihen notwendigen neuen Staatsanleihen mussten nämlich aufgrund des hohen Zinsniveaus Anfang der 80er Jahre (Grafik 3) mit höheren Zinsen ausgestattet werden. Sollte das Zinsniveau von US-Staatsanleihen (4,8% für 1-jährige, 3,6% für 10-jährige, also aktuell etwa 4%) in den nächsten Jahren konstant bleiben, werden die Zinskosten auf bisher nie dagewesene 5% des Volkseinkommens ansteigen (Grafik 6, unterer blauer Punkt). Falls man zur Inflationsbekämpfung 7% Zinsniveau zulässt, würden die Zinskosten in wenigen Jahren auf untragbare 9% des Volkseinkommens ansteigen (Grafik 6, oberer blauer Punkt). Die Differenz zu den heutigen Zinskosten (knapp 2% des Volkseinkommens) würde dem doppelten Wert der gesamten US-Militärausgaben von 2021 entsprechen (3,5% des Volkseinkommens, Quelle: SIPRI Military Expenditure Database). Während des 2. Weltkrieges waren die Staatsschulden der USA auf ähnlich hohe Werte gestiegen wie heute (Grafik 7), aber der Zins wurde konsequent auf ca. 2% gehalten. Damit können die Zinskosten in % des Volkseinkommens kaum höher als 2% gewesen sein, da die Staatsschulden nur kurzzeitig die 100-%-Marke überschritten und schon 1951 wieder auf 78% gesunken waren.

Schon bei Zinskosten von 3% des Volkseinkommens wuchsen die Staatsschulden in den USA ab 1982 schneller als das Volkseinkommen (Grafik 8, rote Linie). Ab 2000 war das Schuldenwachstum für einige Jahre unter Kontrolle; der Grund dafür lag im US-Aktienboom Ende der 90er Jahre, der zu hohen Steuereinnahmen aus realisierten Kursgewinnen führte und damit für einige Jahre Überschüsse im Staatshaushalt ermöglichte (Grafik 9). Seit dieser kurzen Episode steigen die Staatsschulden erneut wesentlich schneller als die Wirtschaftsleistung. Steigende Zinskosten werden diese Entwicklung künftig beschleunigen.

Das grundsätzliche Problem der starken Belastung der Staatsfinanzen aufgrund der hohen Staatsverschuldung schon bei moderaten Zinssätzen lässt sich besonders gut am Beispiel der USA aufzeigen, da es dort die besten Statistiken gibt. In Deutschland (und vielen anderen Ländern) werden wir ähnliche Probleme bekommen. Ab 2019 hat Olaf Scholz in seiner Rolle als Finanzminister in der Zeit negativer Zinsen kaum noch länger laufende Bundesanleihen ausgeben lassen (Grafik 10), so dass bereits jetzt ein erheblicher Teil der Anleihen mit negativen Zinsen fällig wird und durch neu emittierte Anleihen zu wesentlich höheren Zinskosten ersetzt werden muss.

Das Risiko steigender Steuersätze ist hierzulande allerdings vorläufig geringer als in den USA, da die deutschen Unternehmenssteuersätze im internationalen Vergleich ziemlich hoch sind (Grafik 11) und auch die Einkommens-Spitzensteuersätze deutlich über den US-Werten liegen. Schon mit einem Bruttoeinkommen von € 62.810,-, ungefähr das 1,5-fache des Durchschnittseinkommens, zahlt man in Deutschland 42%, ab € 277.826,- 45% Steuern (Quelle: Wikipedia), inklusive Solidaritätszuschlag sind es dann fast 48%.

Die wachsende Bedeutung der Schuldenproblematik zeigen die folgenden Grafiken. Zunächst sehen wir die Verschuldung der großen Volkswirtschaften im Jahr 1980 (Grafik 12) am Ende der Phase steigender Zinsen (Grafik 3). Inzwischen ist die Verschuldung überall massiv angestiegen (Grafik 13).

Dabei ist besonders beunruhigend, dass in den sehr hoch verschuldeten Ländern Japan, Frankreich und neuerdings China auch der Schuldenzuwachs in den letzten 3 Jahren, also der Zeit diverser Krisen (Corona, Inflation, Krieg in der Ukraine, wachsende Entkopplung der westlichen Nationen von China und Russland) zwischen 30% und 45% des Volkseinkommens ausmacht (Grafik 14). Dabei waren die Zinsen bis Anfang 2022 überall extrem niedrig (beispielsweise in den USA, Grafik 3, oder in Deutschland, Grafik 10). Andere Länder bewältigten die Krisen mit einem vergleichsweise moderaten Schuldenzuwachs von ca. 15% des Volkseinkommens.

Das für die Kapitalmärkte entscheidende Fazit dieser Zahlen ist, dass die gestiegenen Zinsen in Verbindung mit dem hohen und weiter wachsenden Schuldenberg dafür sorgen werden, dass künftig vermehrt hochverschuldete Staaten mit den steigenden Zinskosten nicht mehr ohne Hilfe ihrer Zentralbanken zurechtkommen werden.

Auch in der Eurozone entsteht ein wachsendes Rezessionsrisiko. Die Europäische Zentralbank (EZB) berechnet das Geldmengenwachstum für die Mitglieder der Eurozone zurück bis zum Jahr 1981. Bis zum Beginn des Jahres 2023 ist die Geldmenge der Eurozone noch nie geschrumpft, doch seit Januar 2023 hat sich das geändert (Grafik 15a). Die reale Geldmenge (bereinigt um die steigenden Konsumentenpreise) schrumpft sogar massiv (Grafik 15b). Leichte Rückgänge der realen Geldmenge gab es bereits dreimal; jedes Mal folgte darauf eine Rezession.

In der Eurozone ist die Lage aber deutlich weniger gefährlich als in den USA. Die Regierungen der Eurozone haben während der Corona-Pandemie deutlich weniger Geld ausgegeben als die USA (Grafik 16).

Auch deshalb ist die Staatsverschuldung in der gesamten Eurozone mit 91,5% des Volkseinkommens wesentlich niedriger als in den USA (129% des Volkseinkommens, Quelle: Trading Economics). Damit ist das Risiko der steigenden Zinsen für die Staatshaushalte der Eurozone weitaus kleiner als für die USA (Grafik 6), denn neben der Staatsverschuldung sind auch die Zinsen der Eurozone niedriger als in den USA (für 10-jährige Staatsanleihen Ende März 2,5% statt 3,5%, am Geldmarkt 3,5% statt 5%, Quelle: Refinitiv). Die niedrigere Staatsverschuldung ist eine Ursache dafür, dass die Banken in der Eurozone inzwischen deutlich solider sind als die US-Banken. Sie konnten nämlich ihren Bestand an Anleihen erheblich reduzieren, während die US-Banken vermehrt Anleihen gekauft haben (Grafik 17). Kursverluste (wegen steigender Zinsen) auf Anleihen im Besitz von Banken waren im März in den USA die Ursache der Krise einiger kleiner Banken. Ein weiterer Grund für die geringeren Risiken im Bankensektor der Eurozone ist die im Vergleich zu den USA strengere Regulierung, die dazu geführt hat, dass die Kernkapitalquote der Banken (eine erweiterte Definition des Eigenkapitals) in den USA seit der Finanzkrise ab 2008 wesentlich weniger angestiegen ist als in der Eurozone (Grafik 18).

Angesichts der seit langem unzureichenden Steuereinnahmen (Grafiken 4 und 5) und der riesigen Ausgaben während der Corona-Krise (Grafik 16) müssen sich die USA seit 1990 zunehmend im Ausland verschulden (Grafik 19). Auch an dieser Stelle sind höhere Zinskosten künftig ein erheblicher Nachteil, denn dadurch fließt immer mehr Geld ins Ausland ab.

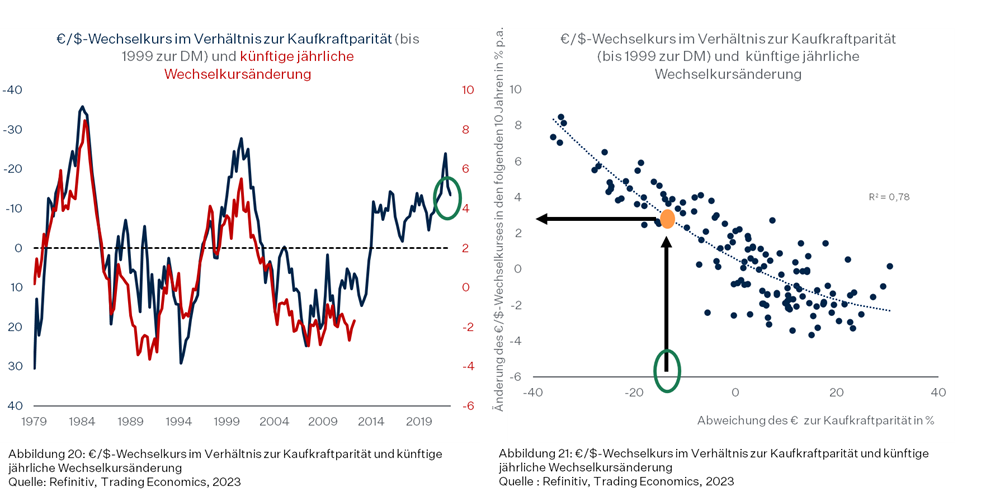

Vor diesem Hintergrund dürfte der US-Dollar, der zur Zeit gegenüber dem € noch 14% überbewertet ist (Grafik 20), in den nächsten 10 Jahren im Vergleich zum € abwerten (Grafik 21), und zwar um ca. 3% p.a..

Damit dürfte auch die starke Outperformance des amerikanischen Aktienmarktes beendet sein, dessen Kurse in € gerechnet seit 2007 zweieinhalb Mal so stark gestiegen sind wie die des europäischen Aktienmarktes. Seit 16 Jahren wurden US-Aktien von einem starken Dollar begünstigt (Grafik 22), aber auch der Boom der Technologieaktien leistete einen erheblichen Beitrag zur US-Outperformance.

Dadurch ist aber auch die Bewertung amerikanischer Aktien seit der Finanzkrise sehr viel stärker gestiegen (Grafik 23) als die Bewertung europäischer Aktien (Grafik 24), nämlich auf das Dreifache des Wertes von 1974 (in Europa nur auf das Zweifache). Entsprechend liegt unsere Ertragserwartung in den USA nur noch bei 3% p.a. (Grafik 25), in Europa dagegen bei 8% p.a. (Grafik 26).

Angesichts der möglichen konjunkturellen Probleme sollte man weiterhin in den konjunkturresistenten Branchen Gesundheit und Basis-Konsumgüter übergewichtet sein (siehe Kapitalmarktausblick vom März 2023, den Sie hier finden). Da die Firmen dieser beiden Branchen außerdem überdurchschnittlich gute Bilanzen haben, dürften sie auch gegen steigende Zinskosten weitgehend immun sein. Generell sollte man aktuell eine neutrale Aktienquote halten, wobei der US-Aktienmarkt insbesondere zu Gunsten Europas und der Schwellenländer deutlich untergewichtet werden sollte.

Abschließend unsere Kernaussagen im Kapitalmarktrückblick vom 23. April 2020, den Sie hier finden:

- Rentenanlagen bleiben unattraktiv und werden auch nicht mehr als Risikosenker funktionieren

- Aktien bleiben attraktiv, eventuelle Kurseinbrüche sind mangels Alternativen nicht nachhaltig

- Einzelhandels- und Büroimmobilien werden durch Online-Handel und Home-Office nachhaltig geschwächt

- Gold wird sich positiv entwickeln

Den Kapitalmarktausblick können Sie auch hier herunterladen.